‘Plain Jane’: Did Lady Jane Grey Habitually Wear Plain and Somber Attire?

Modern accounts of the life of Lady Jane Grey Dudley commonly characterize her as deeply committed to the reformed faith and exceptionally pious. A tradition developed directly out of that characterization to assert that Lady Jane habitually dressed in a simple manner and in somber colors as an outward expression of her inner piety. The tradition became sufficiently pervasive that modern scholarly historians seldom question it, as will be shown. Yet, like many other aspects of the traditional narrative on Lady Jane, the primary source evidence does not support the myth that Jane habitually dressed somberly.[1] This article examines the myth and traces its origins and development together with its impact on depictions of Lady Jane in the visual arts.

The question of Lady Jane’s attire arises most commonly in connection with her portraiture. In 2007, for example, Bendor Grosvenor and David Starkey argued in favor of identifying the sitter in the Wrest Park portrait as Lady Jane based in part on the sitter’s attire (below). While deeming the image a ‘consciously historical portrait,’ they noted that ‘it conformed to the pious image of Jane as a virtuous protestant martyr, not least in the simple costume we know she preferred’ [emphasis added].[2] Subsequent research determined that the sitter is instead Mary Nevill Fiennes, Lady Dacre circa 1541-1558.[3]

by Unknown Artist

Oil on wood panel

29 in. x 21.25 in.

Private Collection

The Wrest Park portrait reemerged in popular media reports early in 2025 as the Courtauld Institute of Art and English Heritage presented new evidence indicating that the costume was altered after the work was originally completed. Rachel Turnbull, Senior Collections Conservator for English Heritage, argued that the new evidence indicates that the portrait had been ‘toned down into subdued, Protestant martyrdom after [Jane’s] death.’[4]

While it is true that the original costume, now hidden, appears to have been different from what is currently visible, another explanation for the change is possible. Following the execution of her husband in 1541, Mary Fiennes’ status was reduced from a member of the titled aristocracy to that of the gentry. She found herself proscribed by Tudor sumptuary laws from wearing her former aristocratic garments. It is entirely possible that Mary Fiennes directed the change herself while she engaged in a two-decade campaign for restoration of the Fiennes’ titles and estates. It would have been to her strategic advantage to exhibit humility during the campaign by altering the manner of her depiction to conform to her lower status.[5]

Lady Jane Grey was fully entitled from birth to wear costly textiles, exotic furs, and lavish jewels as the eldest daughter of one of the highest-ranking peers of the realm. The primary sources are very nearly silent on her manner of dress, however.[6] Her clothing is mentioned only twice in the authentic historical record, both times within the same source. The anonymous Chronicle of Queen Jane, believed to have been written by an eye-witness resident of the Tower of London, reports that Lady Jane wore the same gown at both her trial for treason on 13 November 1553 and at her execution on 12 February 1554. At her trial, Jane

“was in a black gown of cloth, turned down; the cape lined with fese velvet, and edged about with the same; in a French hood, all black, with a black billament, a black velvet book hanging before her, and another in her hand open ….” [7]

Jane’s choice of all black attire at both her trial and her execution undoubtedly reflects a desire to appear humble, penitent, and submissive as she stood before her judges and the executioner. Her costume was entirely appropriate for the nature of both proceedings.[8]

Jane made numerous other public and semi-public appearances prior to 1553, despite a later tradition that she led a life of ‘splendid isolation’ at the Grey family seat of Bradgate Park in Leicestershire.[9] These included grand occasions of state at which all participants customarily dressed in their finest attire to convey their socio-economic status. Both of Jane’s parents played conspicuous roles in the coronation ceremonies and celebrations for King Edward VI in 1547, for example, and Jane almost certainly attended as well. The king states in his personal journal that Lady Jane was likewise present to receive Mary of Guise, Dowager Queen of Scotland, upon the latter’s visit to London on 4 November 1551.[10] But none of those accounts remark on her clothing. That they remain silent on her attire suggests that it was unremarkable and consistent with that of her peers. It seems illogical in the context of the Tudor royal court that plain and somber attire on a grand occasion would have passed without comment from one or more observers.

The source of the myth that Lady Jane habitually dressed somberly lies with her tutor John Aylmer. He included in his An Harbour for Faithful and True Subjects, published in April 1559, a didactic anecdote intended to affirm the suitability of Elizabeth Tudor to serve as monarch despite her gender. Aylmer wrote Harbour as a direct rebuttal to John Knox’s The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women of 1558, itself a denunciation of gynarchy, or rule vested in a woman.[11] The objects of Knox’s polemic were Mary Tudor of England and the Scottish regent Mary of Guise, but First Blast had the potential after November 1558 to be read as a denunciation of Mary Tudor’s heir Elizabeth, as well. Aylmer intended his work as a defense of Elizabeth’s suitability to reign despite the many religious, social, and cultural prohibitions against rule or authority vested in women. Aylmer presented Elizabeth throughout Harbour as a pious and godly follower of ‘right religion,’ which is to say the reformed faith promulgated by Edward VI and Thomas Cranmer through the English Book of Common Prayer. Aylmer wrote of Elizabeth,

“I am sure that her maidenly apparel, which she [Elizabeth] used in King Edward’s time, made the noble men’s daughters and wives to be ashamed to be dressed and painted like peacocks, being more moved with her most virtuous example than with all that ever Paul and Peter wrote touching that matter. Yea, this I know, that a great man’s daughter, receiving from Lady Mary before she was Queen goodly apparel of tinsel cloth of gold, and velvet, laid on with parchment lace of gold, when she saw it, said, ‘What shall I do with it?’ ‘Mary,’ said a gentlewoman, ‘Wear it.’ ‘Nay,’ quod she, ‘that were a shame to follow my Lady Mary against God’s word, and leave my Lady Elizabeth, which followeth God’s word.’ See that good example is oft times much better than a great deal of preaching. And this all men know, that when all the ladies hent up [i.e., take on, assume] the attire of the Scottish skites [i.e., contemptible persons] at the coming in of the Scottish Queen, to go unbridled and with their hair frounced and curled and double curled. She [Elizabeth] altered nothing, but to the shame of them all, kept her old maidenly shamefastness &c.”[12]

Aylmer mimicked the parables of the Bible, offering a simple story to illustrate a moral principle. As with all Biblical parables, the central figure remains unnamed. The rhetorical and didactic focus of the moral lesson of the parable is Elizabeth. Her identity is critical to Aylmer’s larger thesis. The specific identity of the ‘great nobleman’s daughter’ is irrelevant in the given context, however. Aylmer identified her social rank as that of a ‘great man’s daughter’ only to establish that she, unlike her social inferiors, was fully eligible to wear the items named. It remains possible, even likely, that Aylmer deliberately fabricated the tale in its entirety as a fictional example of Elizabeth’s morally upright behavior to counter the negative religious, social, and cultural attributes commonly associated with her gender.

The antiquarian John Strype recalled Aylmer’s parable in 1701 when he wrote his biography of Aylmer. Strype stated that he found the account ‘somewhere’ in Aylmer’s papers but was unable to recall the location precisely. Strype repeated the parable in the context of praising Aylmer’s ‘felicity’ in having had Lady Jane Grey as a pupil early in his career. Strype repeated only the central portion of the above text, beginning with ‘a great man’s daughter’ and ending with ‘which followeth God’s word.’ The larger context of praising the virtues of Elizabeth, specifically, is lost in Strype’s telling. The emphasis shifts instead to the ‘great man’s daughter,’ whom Strype implied through context was Jane Grey.[13] Strype’s relation of the parable is often cited by subsequent authors writing about Lady Jane Grey without mentioning Aylmer’s original and its own quite different context. As a result, the story has become firmly attached to Jane as an example of her piety rather than to Elizabeth as an example of her qualifications to rule.

A careful review of Aylmer’s letters to the Swiss religious reformer Heinrich Bullinger reveals a somewhat different account of Jane’s habits. Aylmer sought Bullinger’s assistance with his young pupil Jane in December 1551.

“It now remains for me to request that … you will instruct my pupil in your next letter as to what embellishment and adornment of person is becoming in young women professing godliness. In treating upon this subject, you may bring forward the example of our king’s sister, the princess Elizabeth, who goes clad in every respect as becomes a young maiden; and yet no one is induced by the example of so illustrious a lady … to lay aside, much less look down upon, gold, jewels, and braidings of the hair. They hear preachers declaim against such things, but yet no one amends her life.”[14]

Aylmer’s letter indicates quite clearly that Lady Jane did not, in fact, dress in accordance with his own estimation of what was appropriate for a young woman professing godliness. And Aylmer’s wording further indicates that his own prior attempts to convince her to amend her ways had proven futile. ‘No one amends her life,’ Aylmer declares, and Lady Jane is clearly the ‘no one’ to whom Aylmer refers.

It is additionally noteworthy that no observers commenting on Lady Jane’s participation in the events surrounding the succession crisis of July 1553 made any mention of her attire. This again suggests that it did not differ noticeably from that of her contemporaries and thus that Jane had not amended her ways after 1551 to accord with Aylmer’s guidance of that December. Most critically, the Protestant martyrologist John Foxe said nothing about Jane habits of dress in his Acts and Monuments of These Latter and Perilous Days despite offering numerous other anecdotes in illustration of her perceived piety.[15] We can only conclude, therefore, that she dressed in the same manner as her aristocratic peers, which is to say she dressed in the fine textiles and conspicuous jewels that Tudor aristocrats customarily wore to convey visually their high rank and socio-economic status.

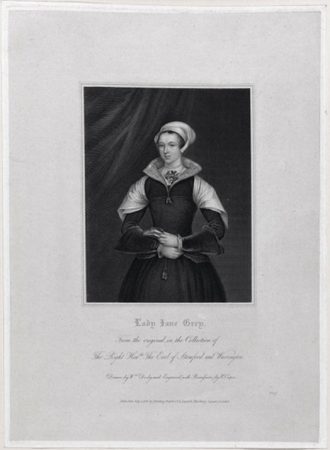

The popular literature on Lady Jane Grey has reinforced the myth that she wore somber attire, either through direct reference to Strype’s version of Aylmer’s parable, through illustrations included in printed texts and that reflect Strype’s telling, or both. David W. Bartlett wrote a biography of Jane in 1853 that was sufficiently popular to merit almost a dozen re-issues over the next half century. Bartlett briefly noted Strype’s anecdote, and he illustrated his volume using Robert Cooper’s already widely published unembellished engraving of the Wrest Park Portrait with an identification as Lady Jane (below, top).[16] Fifteen years later, Agnes Strickland noted in the original and subsequent editions of her enormously popular Lives of the Tudor and Stuart Princesses Strype’s abridged version of Aylmer’s parable, providing a significant vehicle for the dissemination of the myth.[17] Additionally, Strickland repeated Bartlett’s use of Cooper’s engraving in the 1888 edition and in all subsequent editions of her text, visually reinforcing the myth.[18]

by Robert Cooper, 1824

Stipple and line engraving

36.1 x 25.9 cm plate size, 37.8 x 27.5 cm paper size

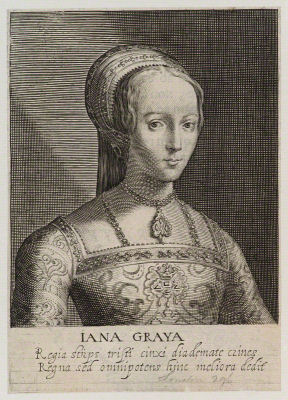

by Charles Picart, 1817

Stipple engraving

9 5/8 in. x 5 7/8 in. (245 mm x 148 mm) paper size

Richard Davey, whose historical novel Nine Days Queen: Lady Jane Grey and Her Times of 1909 enjoyed even greater popularity and consequent influence on the Janeian mythology than did Strickland’s work, did not mention Jane’s habit of dress. He nonetheless used as his frontispiece another already widely published engraving that reproduced the Althorp Portrait sometimes said to depict Jane (above, bottom). In that portrait, the sitter wears relatively simple attire and is seated at a desk reading a religious text.[19] The impression conveyed remains one of simplicity and piety.

Hester Chapman, writing in 1962, repeated Davey’s approach by not mentioning Jane’s attire within her text but instead illustrating her volume with an image that, at first glance, suggests somber attire. The frontispiece to Chapman’s book, as well as the dust jacket, utilized a photograph of a portrait from the National Portrait Gallery long thought to depict Jane (below, left). The sitter’s coat is lined with lynx or ermine fur, however, and she wears a gold necklace. Both the luxurious fur and the gold necklace contradict the myth. But the black color of the coat and the absence of billaments on the hood are consistent with the myth and served as the basis for the former identification of the sitter as Lady Jane.[20] Chapman’s silence on Jane’s attire coupled with the ambiguous illustration result in a mixed impression.

Unknown artist, ca. 1555-1560

Oil on panel

6 1/2 in. (165 mm) diameter

National Portrait Gallery, London

Attributed to Master John, ca.1545

Oil on panel

71 in. x 37 in. (1803 mm x 940 mm)

National Portrait Gallery, London

Alison Plowden, author of the current article on Jane Grey contained in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, penned her first of two studies of Jane and the Grey family in 1986. In the first edition, Plowden cited Aylmer’s letter to Bullinger of December 1551 in which Aylmer sought assistance in persuading Jane to amend her errors in dress.[21] Plowden did not mention Aylmer’s Harbour or Strype’s Life of John Aylmer in the main text, however, instead simply noting their existence in her ‘Note on Sources.’ In contrast to previous accounts of the life of Jane Grey, however, Plowden’s edition is illustrated with a photograph of a portrait from the NPG formerly identified as Jane Grey but now known to depict Katherine Parr (above, right).[22] The sitter is notably dressed in luxurious attire and fine jewels, again in contradiction of the myth.

Plowden reissued the study in 2003, with a change of title and some alterations in the text, to coincide with the 450th anniversary of Jane’s brief reign. The second edition again discusses Aylmer’s letter to Bullinger, but Plowden added the account from Strype.[23] Those written descriptions are supplemented by a photographic illustration of the same NPG portrait used by Chapman as her frontispiece. But while that simplicity of the illustration perhaps implied ‘correct’ dress on Jane’s part, the book jacket to Plowden’s second edition was illustrated with an image derived from the Hastings Portrait of Katherine Parr (below, top). In that portrait, the sitter wears luxurious fabrics and extensive jewels. The Hastings Portrait had served in turn as the reference image for the Van De Passe Engraving of 1620 (below, bottom), published in Henry Holland’s Herωologia Anglica as an authentic portrait of Lady Jane attributed to Hans Holbein.[24] The overall impression conveyed is contradictory and confusing.

Unknown artist, ca.1545

Oil on canvas

38 in. x 26 in.

Private collection

Willem and Magdalene van de Passe, 1620

Line engraving

6 1/2 in. x 4 1/2 in. (164 mm x 115 mm) plate size; 7 in. x 5 1/8 in. (179 mm x 130 mm) paper size

Leanda de Lisle’s collective biography of the three Grey sisters noted without source citation that Jane had a fondness for carefully styled hair and fine clothes.[25] The single illustration of Lady Jane included in the volume is a photograph of the Yale Miniature, which de Lisle rightly noted is ‘controversial’ and may not depict Jane (below).[26] The sitter in the miniature wears a dark gown, but her French hood is richly embellished with gold and jewels, and she wears a necklace of gold links. De Lisle’s work is the first to contradict the traditional mythology asserting that Jane habitually dressed in plain and somber attire, though she did not fully explore the issue.

Unknown artist, ca.1535

Gouache on thin card

1 7/8 in. diameter

Yale Center for the British Arts

The historian Dr Nicola Tallis published her study of Jane Grey in the popular press. In that work, Tallis reaffirmed the traditional mythology. She quoted Aylmer’s letter to Bullinger of December 1551 and paired it with the anecdote from Strype, but she significantly embellished the account. Tallis asserted without citation to any source that the gift of fine textiles supposedly presented to Jane by the Lady Mary was motivated by a desire to see Jane well outfitted for the Scottish Queen Dowager’s visit to England early in November 1551. ‘Mary realized that lavish array meant everything on occasions such as this and would have assumed that the teenage Jane would appreciate such a gesture.’ After quoting first Aylmer’s letter and then Strype’s anecdote, Tallis stated, ‘It now appeared that Jane was determined to be seen as a sober evangelical maiden who favoured plain black and white dress.’[27] Tallis chose as her single illustration of Lady Jane a monumental scene painting by Paul Delaroche (below).[28] The costumes in Delaroche’s depiction are markedly anachronistic, but one of Lady Jane’s attendants nonetheless holds in her lap the rich gown and necklace of pearls and gemstones put off by Jane as she approached the block. As with Plowden, the result is a confused impression of repetition of the myth but illustration with an image that contradicts the myth.

Paul Delaroche, 1833

Oil on canvas

96.8 in. x 116.9 in.

National Gallery, London

The myth acquired a new dimension upon the publication by Melita Thomas in 2022 of her study of several generations of the Grey family. Thomas identified the gift given by Mary to Jane as a ‘magnificent dress,’ or a finished garment rather than raw cloth. Mary presented the gift specifically as a Christmas present, according to Thomas, though gift giving in Tudor England was more commonly associated with New Year’s celebrations than with Christmas. Thomas asserted without source citation that plainness of dress distinguished all ‘godly’ followers of reformism from Roman Catholics and their own resplendent attire. But she simultaneously argued that Elizabeth Tudor’s ‘newfound modesty had more to do with living down the Seymour scandal than religious fervor, but Jane was not to know that.’[29] Thomas’s volume included illustrations, but none were of Jane.

Most recently, author Beverley Adams repeated Thomas’s description of the gift as a finished gown. She simplified the identification of the fabric to cloth of gold exclusively, without mention of velvet or parchment lace of gold. Adams suggested, however, that the gown did not suit Jane’s ‘reserved, sober and rather serious person.’ Jane’s response to the gift was therefore ‘petulant’ and, rather than being motivated by a desire to dress somberly, was inspired instead by a desire ‘not to be seen to be receiving gifts from a catholic [sic].’[30] The first illustration plate in Adam’s volume (below) reproduced the Streatham portrait depicting Jane in the finery common to the English aristocracy of the Tudor period, again in confusing contradiction of the myth.

Unknown artist, after 1594

Oil on panel

33.7 in. x 23.7 in.

National Portrait Gallery, London

Eric Ives wrote the only peer-reviewed study of Jane Grey in 2009. Ives quoted at length from Aylmer’s letter to Bullinger and asserted that Jane ‘clearly … was becoming increasingly interested in clothes.’[31] He also cited Aylmer’s Harbour and suggested that Jane was ‘clearly the person Aylmer had in mind’ in the anecdote.[32] But Ives also quoted Richard Davey’s account of Jane’s entry into the Tower and its description of the lavish gown worn on that occasion, unaware that Davey had entirely fabricated the account.[33] Likewise, Ives’s illustrations include numerous portraits sometimes said to depict Jane and in which the sitter is dressed in aristocratic finery. These include the Houghton and Northwick Portraits, the van de Passe engraving, the Yale miniature, and the Fitzwilliam Portrait.[34] The Wrest Park Portrait is also included, regarding which Ives states, ‘The costume becomes of particular interest because it is unusually plain and wholly lacking in adornment which suggests that it could have originated in a likeness taken when she was a prisoner in the Tower.’[35] Ives offers a personal preference for the Streatham Portrait, however, characterizing it as a ‘persuasive likeness.’[36] And the Streatham Portrait is used on the dust jacket for the volume as a portrait of Lady Jane. Ives therefore appears overall to discount the myth that Jane habitually dressed in plain and somber attire, though he does so only by implication through reference to portraiture rather than directly.

Early portraits of Lady Jane Grey, produced prior to the publication of Strype’s anecdote in 1701 and prior to the appearance of any biographical accounts of Jane, suggest that there was no cultural expectation before the eighteenth century that she should be depicted in plain or somber attire. Four portraits intended by their original artists to depict Jane and that were created between her death in 1554 and Strype’s account of 1701 all depict her wearing finery consistent with that of her aristocratic contemporaries, with one exception.[37] That exception is the Syon portrait commissioned in the second decade of the seventeenth century by the descendants of Jane’s younger sister Katherine Grey Seymour (below).

Unknown artist, after 1610

Oil on wood panel

22 in. x 17 ½ in

Collection of the Dukes of Northumberland

The Syon portrait differs from the other three in that it does depict the sitter wearing all black, though her coat is lined with luxurious lynx fur, and she wears a strand of white beads, probably pearls, around her neck. The Syon portrait was copied from the Berry Hill portrait of circa 1558–1565, however, and the sitter in the Berry Hill portrait is not Jane Grey. She may instead be Jane’s younger sister Katherine as she appeared early in Elizabeth’s reign when Katherine was heir presumptive to the unmarried and childless Elizabeth Tudor.[38] The engraver George Vertue produced in 1748 a widely published engraving that included the Syon copy of the Berry Hill portrait as the central image, thereby lending further credence to the myth that Jane habitually dressed in somber attire after that myth emerged in 1701 (below).

George Vertue, 1748

Line engraving

18 3/8 in. x 22 ¼ in.

An additional early portrait must be considered, though its original artist did not intend it to depict Lady Jane Grey.[39] The Wrest Park portrait noted above gained its identification as Lady Jane sometime in the second half of the seventeenth century, prior to popularization of the myth that Jane dressed somberly. Robert White produced the first engraving of this portrait in 1681, when the painting was still with the Dacre family, doing so with an identification as Lady Jane (below). The Dacres had reidentified the sitter as Jane Grey prior to White’s engraving of the portrait. The re-identification likely stemmed from the Dacres own political and religious affiliations during the English Civil Wars. The Dacre seat of Herstmonceux in Sussex had served as a regular meeting place for leaders of the Parliamentary army, for example, a clear indication of Dacre sympathies.[40] And it must be noted that a second portrait of Mary, Lady Dacre together with her son Gregory was simultaneously reidentified by the Dacres as a portrait of Jane’s mother Frances Brandon Grey, a further marker of the Dacres’ affinity for the Greys of Bradgate.[41] But in producing his engraving, White significantly embellished the sitter’s costume, adding fur trim and jeweled ouches to the bodice of the gown and billaments of goldwork and gemstones to the headdress. White’s embellishments again suggest that no cultural expectation of plain and somber dress yet existed. Robert Cooper’s subsequent engraving noted above faithfully reproduced the Wrest Park portrait, but it did not appear until 1824, over a century after Strype popularized Aylmer’s parable.

by Robert White, 1681

Line engraving

24.6 x 15.7 cm plate size, 32.2 x 19.4 cm paper size

In almost every other instance, portraits with identifying inscriptions added after they were produced or in which the sitter is depicted in somber attire did not become associated with Lady Jane until after the publication of Strype’s account in 1701 and of Cooper’s engraving in 1824. The sitters in those portraits were identified in response to the myth rather than inspiring it.

In sharp contrast, however, at least eighteen historical scene paintings that include Lady Jane and that were produced after 1785 depict Lady Jane either in a white gown or in clothing consistent with that of her peers. She is depicted in dark and sombre attire only in the additional twenty-five scenes of her imprisonment or execution. The failure of non-prison scene paintings to reflect the myth of plain and sombre clothing is likely the result of a deliberate compositional choice by the respective artists rather than a desire to contradict the myth, however. A white gown, in particular, created a visual focal point within the composition while simultaneously reinforcing an attribution to Jane of pious virginal purity, thereby accomplishing the same goal as depicting her in plain dark clothing.

The popular literary and portraiture tradition that Lady Jane Grey habitually dressed in plain and somber attire is a myth. That myth was borne of John Aylmer’s parable about Elizabeth Tudor in which Jane is not named, of John Strype’s quotation of Aylmer’s parable in an unrelated context centered on Lady Jane, and the visual repetition of the myth through the widespread publication and reproduction of Robert White’s engraving in 1824 of the Wrest Park portrait, itself a misidentified portrait of Mary Neville Fiennes, Lady Dacre. The surviving primary source evidence does not contain any indication that Jane dressed differently from her aristocratic peers. We must therefore conclude that she almost certainly dressed in the same luxurious textiles and fine jewels as her peers.

J. Stephan Edwards, PhD, FSA

Palm Springs, California

October 2025

NOTES:

[1] See, for example, J. Stephan Edwards, ‘On the birth date of Lady Jane Grey’, Notes & Queries liv (2007), 240–2; ‘A further note on the date of birth of Lady Jane Grey’, Notes & Queries lv (2008), 146–8; and ‘The final resting place of Lady Jane Grey’, Notes & Queries lxxii 72 (2025), 32–6.

[2] Bendor Grosvenor and David Starkey, Lost Faces: Identity and Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture (London, 2007), 84–6.

[3] J. Stephan Edwards, ‘A life framed in portraits: an early portrait of Mary Nevill Fiennes, Lady Dacre’, The British Art Journal xiv:2 (January 2014), 14–20; ‘Re-Examining the New Evidence for Identifying the Wrest Park Portrait as Lady Jane Grey’, The British Art Journal xxv, forthcoming October 2025.

[4] Pan Pylas, ‘This portrait may be the only one of England’s 9–day queen, Lady Jane Grey,’ APNews.com, 7 March 2025 <https://apnews.com/article/jane–grey–queen–england–portrait–wrest–park–760d15fa05a579e1e8f5c7836df41d4a> (8 March 2025).

[5] J. Stephan Edwards, ‘Re-Examining the New Evidence for Identifying the Wrest Park Portrait as Lady Jane Grey’, The British Art Journal: Online, forthcoming 2025.

[6] Numerous biographies of Lady Jane Grey written in the twentieth century repeat a supposed eye-witness account of her attire upon her ceremonial entry into the Tower of London on 10 July 1553. That account was first presented in 1909 by Richard Davey, but he fabricated the source in its entirety. Richard Davey, Nine Days Queen: Lady Jane Grey and her times (London: Methuen, 1909), 252–3. On the fabrication of the account, see Leanda de Lisle, ‘Faking Jane: on Lady Jane Grey & a historical forgery uncovered’, The New Criterion lxxviii (2009), 77; J. Stephan Edwards, Portraits of Lady Jane Grey Dudley, England’s ‘Nine Days Queen’: Revised Edition (Palm Springs: Old John Publishing, 2024), 183–7.

[7] Anon, The Chronicle of Queen Jane and of Two Years of Queen Mary, edited by John Ggough Nichols (London, 1850), 32 and 56. The meaning of fese as used here is unclear. The Oxford English Dictionary identifies fese as a Middle English variant of the noun ‘fee,’ or the sum paid for admission to an examination. Harvard University’s Chaucer Dictionary identifies fese as a verb meaning ‘to drive away.’ The University of Michigan’s Middle English Compendium defines fese as ‘a blast, or rush.’

[8] Maria Hayward, ‘“We should dress fairly for our end”: The significance of the clothing worn at elite executions in England in the long sixteenth century’, History ci (2016), 222–45 .

[9] Richard Davey, Nine Days Queen: Lady Jane Grey and her times (London: Methuen, 1909), 173.

[10] Edward VI, The Chronicle and Political Papers of King Edward VI, edited by W.K. Jordan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press for the Folger Shakespeare Library, 1966), 93.

[11] John Knox, The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (Geneva, 1558).

[12] John Aylmer, An harborovve for faithfull and trevve subiectes agaynst the late blowne blaste, concerninge the gouernme[n]t of vvemen (Strasbourg, 1559), fols. 49r–v.

[13] John Strype, Historical collections of the life and acts of the Right Reverend Father in God, John Aylmer, Lord Bishop of London in the reign of Queen Elizabeth (London, 1701), 297–8.

[14] Original Letters Relative to the English Reformation, edited by Hastings Robinson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1846), i:277–9. Aylmer references 1 Peter 3:3–4 and 1 Timothy 2:9. Peter counseled women that their ‘apparel shall not be outward with braided hair and hanging on of gold, or in putting on of gorgeous array, but let the inward man of the heart be incorrupt with a meek and a quiet spirit, which before God is much set by’ (Myles Coverdale translation of 1535). Similarly, Paul advises Timothy to instruct women ‘that they array themselves in comely apparel with shamefastness and discrete behaviour, not with braided hair, or gold, or pearls, or costly array, but with such as it becometh women that profess godliness through good works.’

[15] John Foxe, Acts and Monuments of These Latter Perilous Days (London, 1563), v:969–1, v:1542–3.

[16] David W. Bartlett, The Life of Lady Jane Grey (Buffalo: Derby, Orton, and Mulligan, 1853), frontispiece.

[17] Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Tudor and Stuart Princesses, including Lady Jane Gray [sic] and her sisters (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1868), 132. This original edition reproduced a fictional portrait of Jane’s younger sister Katherine Grey Seymour on the frontispiece.

[18] Agnes Strickland, Lives of the Tudor and Stuart Princesses, including Lady Jane Gray [sic] and her sisters (London, 1888 and 1907), frontispiece.

[19] Richard Davey, Nine Days Queen: Lady Jane Grey and Her Times (London: Methuen, 1909), frontispiece; J. Stephan Edwards, Portraits of Lady Jane Grey Dudley, England’s ‘Nine Days Queen’: Revised Edition (Palm Springs: Old John Publishing, 2024), 130–5.

[20] Chapman 1962, frontispiece; Edwards, Portraits, 94–7.

[21] Alison Plowden, Lady Jane Grey and the House of Suffolk (New York: Franklin Watts, 1986), 71.

[22] Edwards, Portraits, 24–7.

[23] Alison Plowden, Lady Jane Grey: Nine Days Queen (Stroud: Sutton, 2003), 64 and 72.

[24] Henry Holland, Herωologia Anglica (Arnhem, 1620), 32; Edwards, Portraits, 18–23, 28–33.

[25] Leanda de Lisle, The Sisters Who Would Be Queen: The Tragedy of Mary, Katherine, and Lady Jane Grey (Hammersmith: Harper Collins, 2008), 34.

[26] Bendor Grosvenor and David Starkey, Lost Faces: identity and discovery in Tudor royal portraiture (London, 2007), 79–83; Edwards, Portraits, 102–7.

[27] Nicola Tallis, Crown of Blood: The Deadly Inheritance of Lady Jane Grey (London: Pegasus Books, 2016), 148–9.

[28] Grosvenor and Starkey, Lost Faces, 79–83; Edwards, Portraits, 102–7.

[29] Melita Thomas, The House of Grey: Friends and Foes of Kings (Stroud: Amberley Press, 2022), 300.

[30] Beverley Adams, The Tragic Life of Lady Jane Grey (Barnsley: Pen and Sword History, 2024), 72.

[31] Eric Ives, Lady Jane Grey: A Tudor Mystery (Chichester: WIley-Blackwell, 2009), 54.

[32] Ibid., 55.

[33] Ibid., 14–15 and 187–8.

[34] Ibid., pl 1, 2, 5, 6 and 9; ; Edwards, Portraits, 54–9, 38–43, 18–23, 102–7, and 70–3, respectively.

[35] Ives, Lady Jane Grey, 17.

[36] Ibid., 16.

[37] In chronological order of production, Figs 9, 10, 6, and the Edwards Portrait. Numerous other portraits that had lost their original identification were re-identified in and after the seventeenth century as Lady Jane Grey, but none were intended by their original artists to depict Lady Jane.

[38] Edwards, Portraits, 146–182.

[39] Several early portraits said to depict Lady Jane Grey are not included in this discussion because they bear identifying inscriptions added long after the original work was completed, and most of those can be identified as fictional or Biblical figures, other women of the period, or as women from Continental countries. Edwards, Portraits, 28–33, 44–9, 108–11, 112–5 and 130–5.

[40] Thomas Barrett–Lennard, An Account of the Families of Lennard and Barrett (privately printed, 1908), 286.

[41] Mary Neville, Lady Dacre; Gregory Fiennes, 10th Baron Dacre (formerly Frances Brandon Grey, Duchess of Suffolk and Adrian Stokes), Hans Eworth, oil on panel, 1559, National Portrait Gallery, London, acc. no. NPG 6855.