Re-examining the New Evidence for Identifying the Wrest Park Portrait as Lady Jane Grey

Widespread reports appeared in the popular media in March 2025 highlighting new evidence intended to support identifying Lady Jane Grey Dudley as the sitter in a portrait included in an exhibition at Wrest Park in Bedfordshire (UK) (below).[1] The Courtauld Institute of Art compiled the new evidence in cooperation with the anonymous owner of the painting and English Heritage, the sponsor of the exhibition. This article examines the new evidence from an alternative perspective and reiterates a previous identification of the sitter as Mary Nevill Fiennes, Lady Dacre.[2]

by Unknown Artist

Oil on wood panel

29 in. x 21.25 in.

Private Collection

The painting is known as the Wrest Park Portrait for having been held at the Wrest Park estate of the Grey Earls of Kent, who were distant cousins of the Greys of Bradgate Park and thus of Lady Jane Grey. But the painting originated in the 16th century with the Fiennes and Lennard family, Barons Dacre of Herstmonceux in Sussex, who had no connection to the Greys of Bradgate. Thomas Lennard, 15th Baron Dacre, sold this painting and others from the Dacre collection in about 1701 to pay off gambling debts. It was purchased by the Greys of Wrest Park, and both the painting and Wrest Park passed in a female line of descent to the Barons Lucas of Crudwell. The painting remained at Wrest Park until the estate was sold in 1918.[3] It is now in a private collection.

The reports mark the second time in 20 years that the Wrest Park Portrait has been put forward as a potentially authentic image of Jane Grey Dudley. Art historian and dealer Bendor Grosvenor and historian David Starkey argued in relation to an exhibition in 2007 at the London galleries of Philip Mould Ltd that the portrait is a posthumous depiction of Lady Jane.[4] Their assertion was challenged by this author in 2014 and Lady Dacre identified as the sitter.[5] But as Peter Moore of English Heritage recently noted, ‘It’s not a closed book on this one.’[6]

Dr Ian Tyers, a leading expert in the dendrochronological analysis of paintings on wood panels, offered the first item of ‘new’ evidence. Tyers determined that the panel was most likely used between 1539 and 1571, according to media reports.[7] Lady Jane was executed in February 1554, at roughly the halfway point of the given timespan. Yet a previous study by an unidentified dendrochronologist had already produced a date of usage after 1541.[8] Tyers’s fresh study, although differing from the previous one by only two years, reportedly ‘allowed researchers to determine that the painting may indeed have been made during Grey’s lifetime’.[9] The new dendrochronological evidence does not, however, eliminate Lady Dacre as the sitter.

Mary Nevill (sometimes spelled Neville) married Thomas Fiennes, 9th Baron Dacre in 1536 at the age of just 12 years. Baron Dacre was executed in June 1541 following a conviction for murder, leaving Mary a widow at the age of sixteen. The Dacre titles and estates were forfeited to the Crown, and Mary was consequently demoted from the aristocracy to the gentry.[10] A date of usage after either 1539 or 1541 correlates with both Lady Jane Grey Dudley and Mary Nevill Fiennes, the latter of whom survived until after 1578. The new dendrochronology evidence therefore offers nothing new to determine the identity of the sitter.

A cargo mark appears on the back of the boards, a detail not revealed prior to the recent Courtauld study. Media reports note that an ‘identical’ mark appears on the back of an unidentified portrait of Jane’s cousin, King Edward VI.[11] The reports seem to imply that the presence of an identical mark on a royal portrait indicates that this must also be a ‘royal’ portrait. Yet such import marks were common and not limited to royal portraits. Most of the oak wood for English panel paintings was imported from the Eastern Baltic region near modern Latvia and Lithuania. The Tudor administration routinely granted import monopolies on various commodities, with only one company or individual authorized to import certain types of goods into England. If such a monopoly was granted for the importation of either cut lumber or finished wood panels, it is reasonable to expect that the same cargo mark would appear on all shipments to detect and to deter smuggling. And it is logical, in turn, that multiple paintings depicting a very wide variety of both royal and non-royal individuals might bear the same import monopoly mark. Even in the absence of an import monopoly, the market for wood panels in England was limited, and so one would expect a correspondingly limited number of importers and a repetition of importers’ marks on a wide variety of paintings and portraits. The import mark on the Wrest Park Portrait does not support any specific sitter identification.

The Wrest Park sitter’s face exhibits certain scratches ‘suggesting a deliberate iconoclastic attack on her legacy as a Protestant martyr’, according to the Courtauld (detail, above).[12] The Times described the scratches as ‘similar to ones made on a depiction of Grey which is held by the National Portrait Gallery’.[13] The latter assertion is not, however, strictly true. The marks on NPG 6804 are obvious ‘X’s and are placed directly over both eyes, the nose, and the mouth, as if to cancel out those features (‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’). They are also thinly incised, as if made by a very sharp knife (detail, below).

In contrast, the marks on the Wrest Park Portrait are a series of individual linear scratches of varying length and significant width over the entire left side of the sitter’s face. We can take this further. If the scratches on the Wrest Park Portrait are the result of deliberate defacement in an act of iconoclasm, it seems odd that the right eye remains unaffected, given that both eyes are defaced in NPG 6804. Similarly, the vertical scratch associated with the mouth is situated at the margin of the lips rather than over their centre, as seen in NPG 6804. It is equally possible, even, more likely, that the marks result from accidental damage. Household inventories document the painting moving about between a variety of Dacre residences, including Belhus (Essex), Herstmonceux (Sussex), and Knole (Kent), as well as the residences of subsequent owners after 1918.[14] The positioning of the marks on NPG 6804 are deliberate, as one would expect with an act of iconoclasm; those on the Wrest Park Portrait appear more random, as if from accidental damage, perhaps during a move of the kind suggested.

Promoters of the current exhibition at Wrest Park note, ‘Many versions of the painting were made and have associations either with [Jane] Grey or her family.’[15] The statement is a logical fallacy if intended to suggest that the sheer quantity of copies and variants serves as reliable verification of the identity of the sitter in the original. Robert White produced the first engraving of this portrait in 1681, when the painting was still with the Dacre family, although he significantly embellished the costume (below).[16]

by Robert White, 1681

Line engraving, 24.6 x 15.7 cm plate size, 32.2 x 19.4 cm paper size

The Dacres had already reidentified the sitter as Jane Grey by then, probably as an expression of their own political and religious affiliations during the English Civil Wars. The Dacre seat of Herstmonceux in Sussex had served as a regular meeting place for leaders of the Parliamentary army, for example, a clear indication of Dacre sympathies.[17] It must be noted that a second portrait of Mary, Lady Dacre, together with her son Gregory was simultaneously reidentified by the Dacres as a portrait of Jane’s mother Frances Brandon Grey, a further marker of the Dacres’ affinity for the Greys of Bradgate.[18]

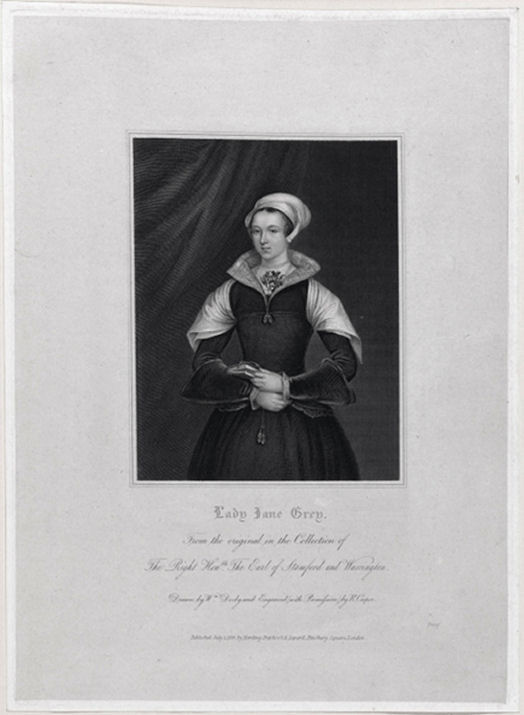

White’s engraving was published in the first edition of the second volume of Gilbert Burnet’s ‘runaway bestseller’ The History of the Reformation of the Church of England.[19] The image was one of the first widely published engravings of Jane, and it became very popular, as Burnet’s History was reissued in four successive editions and reprinted dozens of times.[20] Another engraver, Robert Cooper, produced in 1824 a second engraving that more faithfully reproduced the original painted portrait, increasing the visibility and popularity of the image as a supposedly authentic portrait of Lady Jane (below).[21]

by Robert Cooper, 1824.

Stipple and line engraving, 36.1 x 25.9 cm plate size, 37.8 x 27.5 cm paper size

Cooper’s engraving was reproduced repeatedly after 1824 in reprints of Edmund Lodge’s Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain.[22] Cooper’s engraving remains readily available today as a portrait of Lady Jane through a wide variety of popular online auction sites.

The original painting was also repeatedly reproduced in oil on canvas during the 18th century, after the reidentification of the sitter as Jane Grey, for use in various residences owned by the Dacres and their successors the Earls and Dukes of Kent, including their Enville Hall and Dunham Massey estates.[23] But quantity does not necessarily equate with authenticity. The Althorp Portrait has also been published repeatedly as an engraving and as a supposedly authentic portrait of Jane Grey, yet it indisputably antedates Jane’s birth and depicts a fictionalized Mary Magdalene.[24] The existence of numerous post hoc reproductions does not in itself support identifying the sitter as Lady Jane Grey.

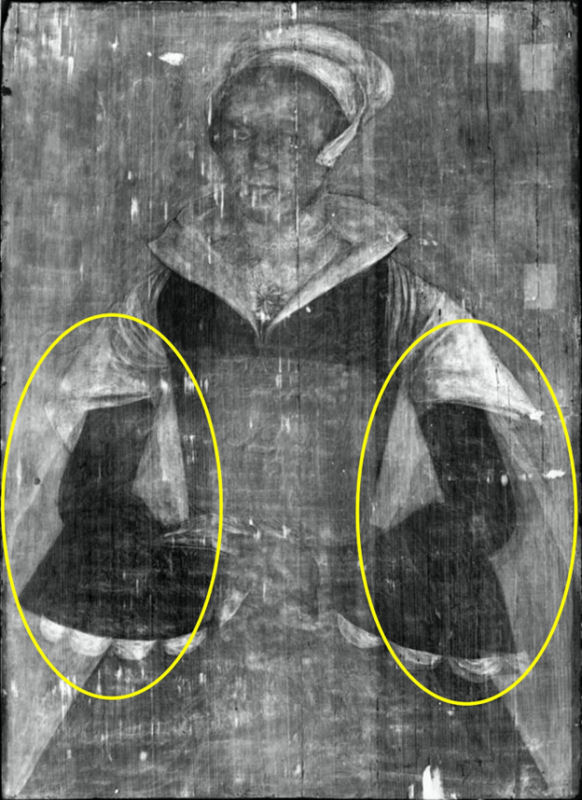

Infrared reflectography studies conducted by the Courtauld reveal alterations to the costume, particularly the addition of a neckerchief over the sitter’s shoulders. The Courtauld argues that the neckerchief may conceal decorative detailing on the dress, and dating of the addition is simply limited to ‘sometime after the original image’s completion’.[25] White’s engraving of 1681 includes the neckerchief, and so the alteration must have been made prior to that year. White added significant detailing on the bodice of the dress, but that detailing is not apparent in the infrared reflectography image, indicating that it may be entirely de novo with respect to the engraving. It is more likely that White added the decorative details in an effort to make the sitter appear appropriately regal. The belief that Jane Grey habitually dressed in sombre attire is a myth that did not emerge until the first quarter of the 18th century, at least a quarter century after White, through a misremembrance by John Strype published in his Historical Collections of the Life and Acts of John Aylmer.[26]

The Courtauld further argues, ‘The sitter had previously appeared with a scarf instead wrapped around her lower arms, which would be consistent with other depictions of Grey.’[27] Among the roughly three dozen surviving portraits said to depict Jane Grey, only one other depicts the sitter wearing a neckerchief over either the shoulders or lower arms. The Pickering Portrait is now lost, and it has historically never been well known to the public.[28] It is remarkably similar to the Wrest Park Portrait, however, suggesting a link between the two. The premise that ‘other depictions’ of Jane include a neckerchief is essentially false.

Similarly, the Courtauld and English Heritage argue that the cap now seen covering the sitter’s hair may conceal a ‘fancier headpiece’ or hood, and that a veil may have been present originally. A veil, properly termed a ‘fall’, of black fabric did customarily attach to the back of French hoods and envelope the hair. Yet neither a hood nor a fall are readily discernible in the published infrared reflectography images.[29] Their possible presence seems to be purely speculative.

It is argued that the alterations to the costume were made in a deliberate effort to make the image conform to one of ‘subdued, Protestant martyrdom’.[30] Despite a thorough search of the literature, this author found no scholarship indicating that plain white hoods and white neckerchiefs over the shoulders are iconographic symbols denoting either Protestantism or martyrdom.[31] In fact, numerous portraits surviving from the Tudor period include similar or identical costume elements worn by women who were demonstrably neither Protestant nor martyrs. See, for example, Hans Holbein’s portraits: of Jane Pemberton Small (c1536) (below, left); of the wife of a servant of Henry VIII (1534) (below, center left); of an unidentified woman dated 1541 (below, center); and of a lady with a squirrel (below, center right); as well as a portrait by an unknown artist depicting Alice Bradbridge Barnham and her sons Martin and Steven, of about 1557 (below, right).[32] The common thread among these women is neither their religion nor martyrdom. It is instead their socio-economic status. Small was the wife of a cloth merchant, for example, while Barnham was a silk merchant in her own right. Another is explicitly identified as the wife of one of Henry VIII’s servants. None shares Lady Jane Grey’s aristocratic status.

The published infrared reflectography image of the Wrest Park Portrait reveals coverings over the arms that are more likely farthingale sleeves rather than a plain white neckerchief (below, highlighted within yellow ellipses).[33] Such sleeves were often made of rich fabrics and heavily embroidered. Wearers folded the sleeves back up the arm to display the fineness of their lining and to display equally fine undersleeves.

As noted above, Mary Nevill Fiennes’ socio-economic status changed from titled aristocrat to gentry upon the execution of her husband in 1541. While her husband Thomas lived, she was eligible under existing sumptuary laws to wear clothing permitted to those with the rank of baron. Those laws explicitly limited the wearing of velvet, satin, damask, fabrics with gold or silver embroidery, and chains of gold or gilt worn as necklaces or bracelets to persons of the rank of baron or higher. The penalty for those of lesser rank doing so was forfeiture of the offending items.[34] In the absence of any evidence to support a specific timeframe for the changes to the costume, it remains entirely possible that the painting was altered at Lady Dacre’s instruction and during her own lifetime to conform visually to sumptuary restrictions associated with her reduced status between 1541 and 1558.

Summary

The individual pieces of evidence detailed in the recent media reports, while useful for more thoroughly documenting the portrait, contribute little or nothing toward reliably identifying the sitter. The rhetorical book to which Peter Moore referred may not yet be closed, but the preponderance of evidence indicates that the portrait depicts Mary Nevill Fiennes, Lady Dacre, consistent with her gentry status between 1541 and 1558. It was relabelled, probably deliberately so, as Lady Jane Grey in the 17th century by Lady Dacre’s descendants and heirs in the fourth generation in an effort visually to convey their sympathies with the Protestant Parliamentarian party during the English Civil Wars and Commonwealth period. The Dacres may have been encouraged in their reidentification of the sitter as Jane, not because of her clothing, but rather because of the presence in the sitter’s hand of a book, an enduring iconographic trope for Lady Jane Grey that denoted her exceptional intellect and learning.[35]

J. Stephan Edwards, PhD, FSA

Palm Springs, California

October 2025

NOTES:

[1] Sonja Anderson, ‘Does This Mysterious Portrait Depict Lady Jane Grey, the Doomed Queen Who Ruled England for Nine Days in 1553?’, Smithsonian Magazine online edition, 10 March 2025 (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/does-this-mysterious-portrait-depict-lady-jane-grey-the-doomed-queen-who-ruled-england-for-nine-days-in-1553-180986198/).

[2] Grosvenor and Starkey, Lost Faces, 85.

[3] Jo Lawson-Tancred, ‘Is This the Only Known Portrait of Lady Jane Grey, the Doomed Teen Royal?’, ArtNet.com, 7 March 2025 (https://news.artnet.com/art-world/is-this-the-only-known-portrait-of-lady-jane-grey-the-doomed-teen-royal-2616092).

[4] Lady Dacre succeeded in reclaiming her late husband’s titles and estates in November 1558, and she commissioned Hans Eworth to produce a portrait of herself and her son Gregory Fiennes, 10th Baron Dacre, in celebration of their rehabilitation. That portrait is now on permanent display at the National Portrait Gallery, London. See Mary Nevill, Lady Dacre and Gregory Fiennes, 10th Baron Dacre, Hans Eworth, oil on panel, 1559, 50 x 71 cm., National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG 6855.

[5] Lawson-Tancred.

[6] Ibid.

[7] See, for example, Katy Prickett, ‘Is this the face of teenage queen Lady Jane Grey?’, BBC.com, 6 March 2025 (https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4g08z0wnvxo); Jack Blackburn, ‘Is this the face of the nine-day queen? Lady Jane Grey goes on display’, The Times, 7 March 2025 (https://www.thetimes.com/uk/history/article/nine-day-queen-lady-jane-grey-bedfordshire-82tlqx9wl); Amarichi Orie, ‘Is this the only known portrait of England’s doomed “Nine Days Queen”?,’ CNN.com, 7 March 2025 (https://www.cnn.com/2025/03/07/style/lady-jane-grey-portrait-england-intl-scli-gbr/index.html).

[8] See J Stephan Edwards, ‘A life framed in portraits: An early portrait of Mary Nevill Fiennes, Lady Dacre’,’The British Art Journal, XIV, 2 (January 2014), 14–20.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Bendor Grosvenor and David Starkey, ‘English School, mid-sixteenth century, Portrait of Lady Jane Grey (d.1554) (?)’, Lost Faces: Identity and Discovery in Tudor Royal Portraiture, exh cat., Philip Mould Ltd, London 2007, 85–86.

[11] Edwards, ‘A Life Framed in Portraits.’

[12] Blackburn, ‘Is this the face of the nine-day queen?’

[13] Blackburn, ‘Is this the face of the nine-day queen?’

[14] J Stephan Edwards, Portraits of Lady Jane Grey Dudley, England’s ‘Nine Days Queen’: Revised Edition, Palm Springs 2024, 60–65.

[15] Blackburn, ‘Is this the face of the nine day queen?’

[16]1 Called Lady Jane Grey, Robet White, line engraving, 1681, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D31627.

[17] Thomas Barrett-Lennard, An Account of the Families of Lennard and Barrett, privately printed, 1908, p286.

[18] See n10 above.

[19] Gilbert Burnet, The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, The Second Part, of the progress made in it till the settlement of it in the beginning of Q[ueen] Elizabeth’s reign, London, 1681.

[20] Pages torn from Burnet’s History and containing the engraved image of Jane Grey continue to be offered regularly on popular internet-based auction sites such as eBay.

[21] Called Lady Jane Grey, Robert Cooper, 1824, line engraving, 36 x 26 cm plate size, 38 x 27.5 cm paper size, National Portrait Gallery, London, NPG D36349.

[22] Edmund Lodge, Portraits of Illustrious Personages of Great Britain, 8 vols, London, 1824, II, f20v.

[23] Edwards, Portraits, 63.

[24]Ibid, 140–145.

[25] Tancred-Lawson.

[26] Article by this author forthcoming in a separate publication.

[27] Tancred-Lawson.

[28] Edwards, Portraits, 122–125.

[29] Amarichi Orie.

[30] Prickett.

[31] Costume historian Lou Taylor identifies the style of white hood seen in the Wrest Park Portrait as a ‘Paris hood’ and associates them primarily with widowhood, although they are also seen on married women. See Lou Taylor, Mourning Dress: A Costume and Social History, London 2009, 52.

[32] See Jane Pemberton Small, Hans Holbein, watercolor on vellum, c1536, miniature, Victorian and Albert Museum, accession number P.40&A-1935; Wife of a servant of King Henry VIII, Hans Holbein, oil on lime panel, 1534, miniature, Kunsthistorisches Museum, acc. no. GG 6272; Portrait of a Woman with a White Coif, Hans Holbein, oil and tempera on panel, 1541, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, acc. no. M.44.2.9; A Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling (Anne Lovell?), Hans Holbein, c1526–28, oil on wood panel, National Gallery, London, acc. no. NG6540; Alice Bradbridge Barnham and her son Martin and Steven, British artist, oil on wood panel, 1557, Denver Museum of Art, acc. no. 2021.32.

[33] Nadia Khomami, ‘Sole portrait of England’s “nine-day queen” thought to have been identified by researchers,’ The Guardian online, 6 March 2025 (https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2025/mar/07/sole-portrait-of-england-nine-day-queen-lady-jane-grey-thought-to-have-been-identified-by-researchers).

[34] 6 Hen.VIII, ca.1., 7 Hen.VIII, c.6.

[35] Edwards, Portraits. See the Norris, Streatham (NPG6804), Houghton, Fitzwilliam, Somerley, Rotherwas, Huntington, South Carolina, Althorp, and Madresfield Portraits as well as the Audley End copy of the Syon Portrait.